Trillions of microorganisms thrive within our gastrointestinal tract, and these are collectively known as the gut microbiome. These bacterial species are crucial to our survival, and we wouldn’t be without them. A symbiotic relationship between our own cells are theirs ensures overall health is maintained, but what can we do to help this relationship, or more importantly, what happens if we don’t tend to it as best as we should?

Prebiotics: “A dietary prebiotic is a selectively fermented ingredient that results in specific changes, in the composition and/or activity of the gastrointestinal microbiota, thus conferring benefit(s) upon host health.” – (International Scientific Association of Probiotics and Prebiotics, 2010)

Naturally found in the cell walls of plants exists a type of resistant carbohydrate known as ‘Fibre’, which are a class of prebiotics. These compounds cannot be digested within our gut, but simply pass on through until they reach our intestines. Here, our gut bacteria make good use of these by ‘feeding’ off them for energy thus influencing their overall growth and activity. Additionally, short chain fatty acids can be formed from degradation of prebiotics, which are then able to travel into the blood stream and positively affect organs outside of our gut realm. Sources of fibre include oats, wholegrains, cereals, fruits, and vegetables.

Table 1. Common food sources and their fibre content per 100g.

| Source | Fibre Content per 100g |

| Wholewheat pasta | 3.5g |

| Multi-seed bread | 8.2g |

| Wholemeal bread | 6.8g |

| Weetabix cereal | 10g |

| Fruit and fibre cereal | 9g |

| Oats | 8.3 |

| Bulgur wheat | 2.2g |

| Quinoa | 3.2 |

| Kidney beans | 7.8g |

| Chickpeas | 6.1 |

| Green lentils | 4.4g |

| Apple (skin on) | 1.8g |

| Banana | 4.2g |

| Raspberries | 6.2g |

| Pear (skin on) | 2.2g |

| Raw carrots | 2.7g |

| Steamed broccoli | 2.3g |

| Boiled potatoes (skin on) | 3.3g |

| Peanuts | 6.3g |

| Almonds | 5.6g |

We can best promote growth and diversity of beneficial gut bacteria by consuming adequate fibre, but also increasing our intake of ‘polyphenols’, a group of compounds found in plants, such as berries, citrus fruits, broccoli, plums, red wine and coffee. We should aim to eat 5 portions of different fruits and vegetables each day (skin included where possible), whilst increasing our intake of wholegrain varieties of foods such as breads, rice, pasta, and cereals. This will help us work towards our 30g/ day fibre intake goal, whilst supporting our gut microbiome. Be sure to slowly increase your fibre intake due to the possible side effects it can have on the gut if introduced too quickly i.e., bloating, stomach pains.

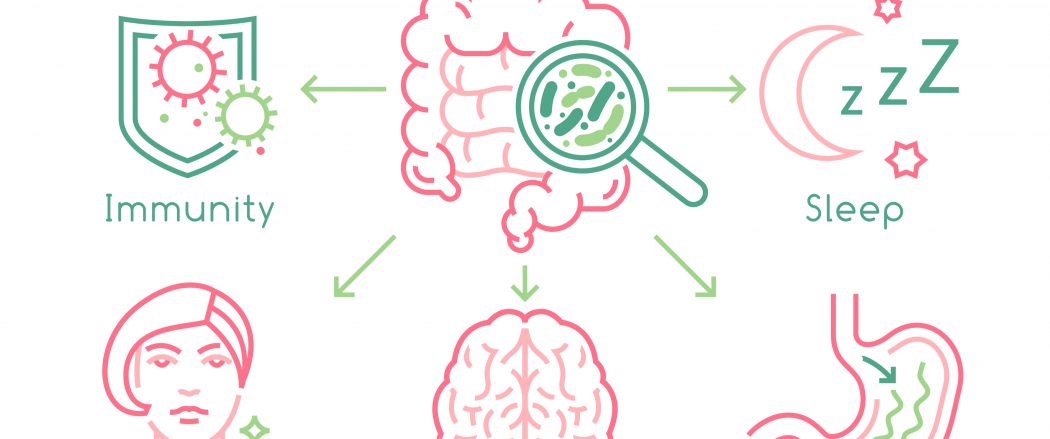

Beneficial outcomes of a diverse gut microbiome include increased immune system functioning, increased antioxidant activity, increased insulin sensitivity and reduced inflammation. There is also a positive correlation between increased fibre intake and a lower BMI.

Fig 1. An illustration of the positive effects of increased prebiotic intake on long term health outcomes along with the negative associations of increased saturated fat and sugar intake, which are typical of a western diet. (Valdes et.al, 2018)

Now the health benefits of increasing prebiotic intake have been outlined, it is also worth mentioning the negative effects of a diet low in prebiotics. A typical western diet is generally high in saturated fats, sugars, and salt which each have their own negative health effects independently. Our microbiome is also influenced by an increase of these foods, though not for good reasons. This type of diet forms what is known as ‘gut dysbiosis’, by which the balance between ‘good and bad’ bacteria is shifted, favouring the latter. When this happens, we increase our risk of hindered immune support, cardiovascular disease, increased inflammation, and even an increased chance developing anxiety and depression.

Our gut is directly linked to our brain via the HPA axis, or simply put the ‘gut to brain axis’. This is where the phrase ‘our gut is our second brain’ comes from, as how the gut is affected can then influence brain activity, hence the increased risk of mood disorders.

The key takeaway from this article is that our microbiome is crucial to our overall survival. We must ensure a diverse culture is present within our gut to positively effect our overall health in the long term. A typical western diet high in saturated fat, sugar and salt should be exchanged for one much higher in plant-based foods, which will help increase both prebiotic and polyphenol intake, thus improving the diversity of our gut microbiome and our overall wellbeing.

- Binns, N., 2013. Probiotics, prebiotics and the gut microbiota. Brussels: ILSI Europe. https://ilsi.org/publication/probiotics-prebiotics-and-the-gut-microbiota/

- Davani-Davari D, Negahdaripour M, Karimzadeh I, et al. Prebiotics: Definition, Types, Sources, Mechanisms, and Clinical Applications. Foods. 2019;8(3):92. Published 2019 Mar 9. doi:10.3390/foods8030092 https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC6463098/

- Gibson, G., Hutkins, R., Sanders, M. et al. Expert consensus document: The International Scientific Association for Probiotics and Prebiotics (ISAPP) consensus statement on the definition and scope of prebiotics. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol 14, 491–502 (2017). https://www.nature.com/articles/nrgastro.2017.75

- Marcel Roberfroid, Prebiotics: The Concept Revisited, The Journal of Nutrition, Volume 137, Issue 3, March 2007, Pages 830S–837S, https://doi.org/10.1093/jn/137.3.830S

- Valdes A M, Walter J, Segal E, Spector T D. Role of the gut microbiota in nutrition and health BMJ 2018. https://www.bmj.com/content/361/bmj.k2179

By Eugene Gristock, BSc, ANutr

Prebiotics and The Gut Microbiome